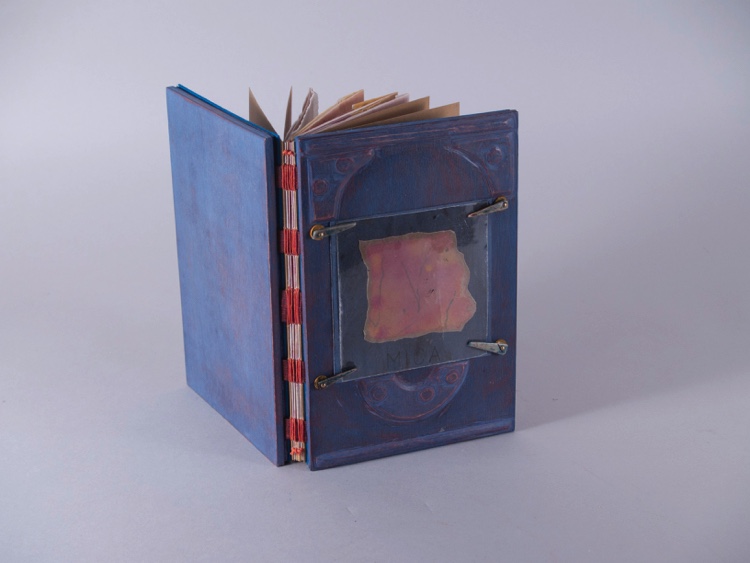

Mica

Details

-

© 2009

- Dimensions (in inches): 8 x 5.25 x 1

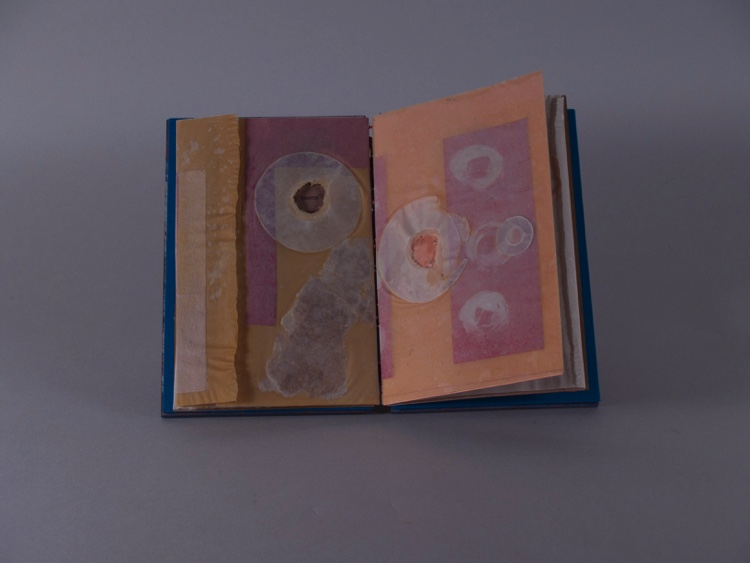

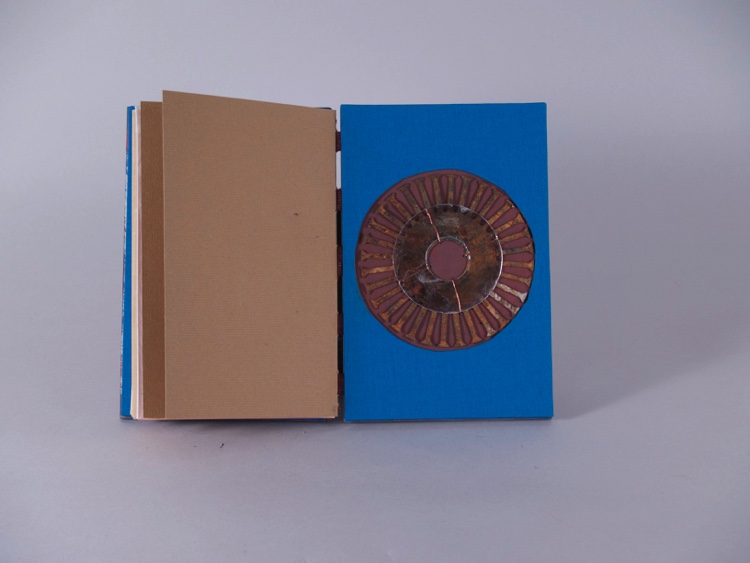

- Materials:birch plywood, paper (including abaca HMP with inclusions), mica, rusted metal, wire, book cloth, laserprinting, museum board, thread

- Collection of:University of Louisville Fine Arts Library

More

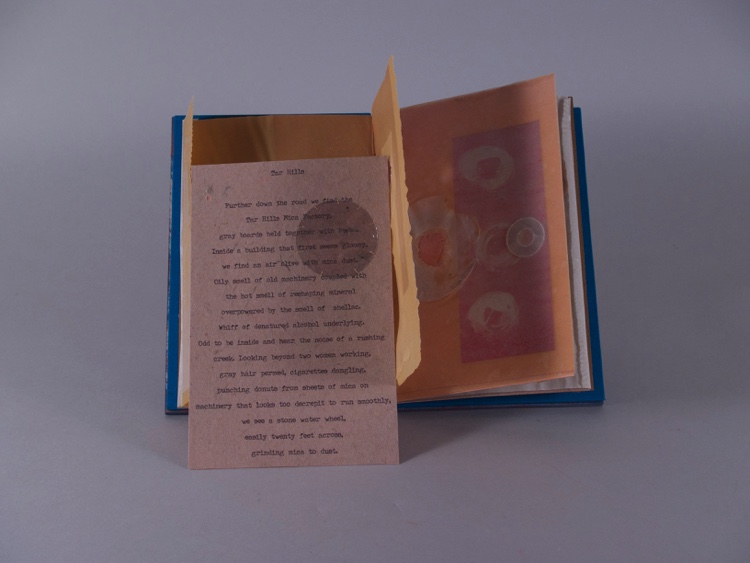

I made this book after spending a day in North Carolina, wading in a stream filled with mica chunks. The pages are sewn on tapes with dimensional wooden covers. Front cover is multi-dimensioned wood with original painting behind mica. Inside back cover has recessed area with metal, wire and mica. Text block is of handmade paper/mixed media in a wrap-around format devised to expose only glimpses of each page until the wrappers are opened. Text is a series of anecdotes around various quests in the southeastern US for the mineral mica. With contributions from Heidi Zednik. The covers were created under the tutelage of Dolph Smith at Arrowmont.

Text:

A near perfect day, wading into a chilly stream.

Enticed by the lure of rumor;

“there is mica in that stretch of stream”.

Big chunks, smaller nuggets of tangible shine.

We gather, then carry them ashore in

pockets overflowing, temporarily marsupial

with pouches fashioned from rolled up shirts.

I rarely look at the photographs from that day,

preferring instead the reminder that comes when

sunshine’s warmth touches my outer ear.

The warmth that is like no other

recalls bearing witness to moments of

trust, connection and lust.

Treasured state mine to cherish

as long as sunshine sparks memory.

Tar Hills

Further down the road we find the

Tar Hills Mica Factory,

gray boards held together with kudzu.

Inside a building that first seems gloomy,

we find an air alive with mica dust.

Oily smell of old machinery coupled with

the hot smell of reshaping mineral

overpowered by the smell of shellac.

Whiff of denatured alcohol underlying.

Odd to be inside and hear the noise of a rushing

creek. Looking beyond two women working,

gray hair permed, cigarettes dangling,

punching donuts from sheets of mica on

machinery that looks too decrepit to run smoothly,

we see a stone water wheel,

easily twenty feet across,

grinding mica to dust.

Buoyed by the promise of potential

raw materials make, we leave with

sheets of mica, clear, speckled, smooth.

Mica washers, thicker and less fine,

a yearning to take away

more than I can afford,

a promise to one another

that we will return.

Later,

I describe to a sculptor who lives

nearby my discomfiture at

being ruled by an acquisitive nature,

so often held in check.

She says ‘I’ve lived here for thirty years,

always sure that the mica factory will shut down.

The mica now comes from India,

the employees are no longer all family.

Still they toil.”

We laugh,

imagining the rotted wood at last falling,

leaving a shell of kudzu,

while the steady work of transforming

imported mineral continues.

A near perfect day, wading into a chilly stream.

Enticed by the lure of rumor;

“there is mica in that stretch of stream”.

Big chunks, smaller nuggets of tangible shine.

We gather, then carry them ashore in

pockets overflowing, temporarily marsupial

with pouches fashioned from rolled up shirts.

I rarely look at the photographs from that day,

preferring instead the reminder that comes when

sunshine’s warmth touches my outer ear.

The warmth that is like no other

recalls bearing witness to moments of

trust, connection and lust.

Treasured state mine to cherish

as long as sunshine sparks memory.

Tar Hills

Further down the road we find the

Tar Hills Mica Factory,

gray boards held together with kudzu.

Inside a building that first seems gloomy,

we find an air alive with mica dust.

Oily smell of old machinery coupled with

the hot smell of reshaping mineral

overpowered by the smell of shellac.

Whiff of denatured alcohol underlying.

Odd to be inside and hear the noise of a rushing

creek. Looking beyond two women working,

gray hair permed, cigarettes dangling,

punching donuts from sheets of mica on

machinery that looks too decrepit to run smoothly,

we see a stone water wheel,

easily twenty feet across,

grinding mica to dust.

Buoyed by the promise of potential

raw materials make, we leave with

sheets of mica, clear, speckled, smooth.

Mica washers, thicker and less fine,

a yearning to take away

more than I can afford,

a promise to one another

that we will return.

Later,

I describe to a sculptor who lives

nearby my discomfiture at

being ruled by an acquisitive nature,

so often held in check.

She says ‘I’ve lived here for thirty years,

always sure that the mica factory will shut down.

The mica now comes from India,

the employees are no longer all family.

Still they toil.”

We laugh,

imagining the rotted wood at last falling,

leaving a shell of kudzu,

while the steady work of transforming

imported mineral continues.

yakyak