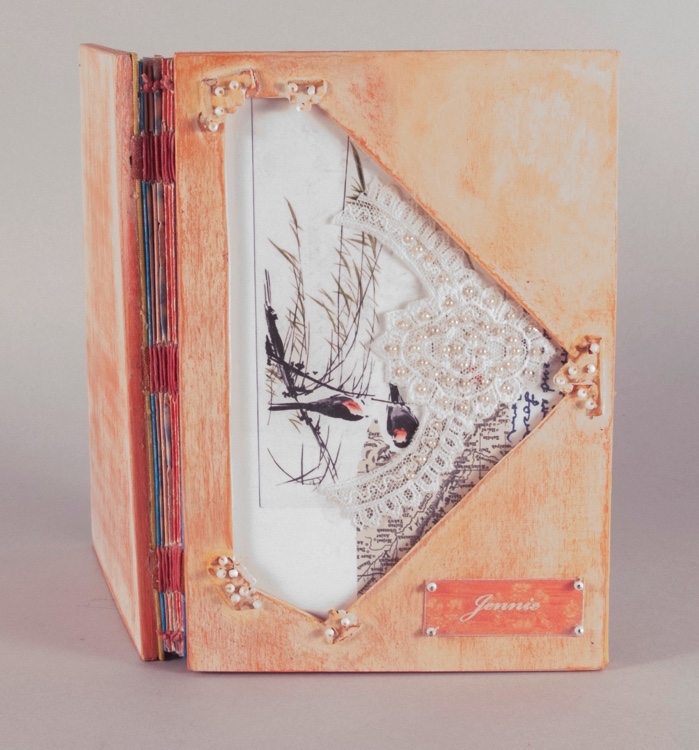

Jennie

Details

-

© 2014

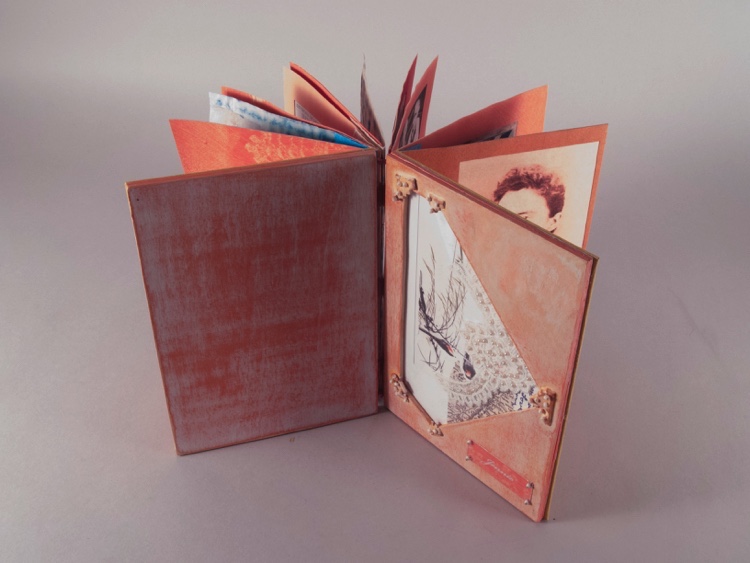

- Dimensions (in inches): 7.5 x 5.25 x 1.25

- Materials:Covers: birch plywood, bone beads, museum board, book cloth, lace, seed beads, color print, etched mica, steel pins, milk paint. Text block: various papers (paste and printed papers, handmade papers with embedded hand-written letters, airmail letter stationary), tyvek, acrylic, digital photographs, ink, laser transfer, thread, bookcloth, mylar.

- Collection of: artists collection (available)

More

A collection of photographs, newspaper clippings, letters and text by the artist featuring the artist's great-great-aunt Jennie. "Jennie was a remarkable woman who made quite an impression on me when I was young, and whose impact on my life has continued throughout. This book, part of the Lovely and Amazing Series of works created from an inherited archive, honors both her life and my memories of her."

My great, great-aunt, Janey Ruth, born in 1873, spent her elder years living in the house my father grew up in, cared for by her niece; my father’s aunt and guardian. As a young child I was impressed by her age, wrinkles, frailty but also by the vigor of her mind and spirit. She enchanted me, her presence so brilliant that my memories of her still shine.

She went by the name Jennie and lived a life full of adventure. A teacher during her working life, the knowledge she accumulated through decades of a lifestyle governed by curiosity and an adventurous spirit made a big impression on my young self. I longed to share her command of algebra, geometry and trigonometry, so rich with mysterious symbols and equations.

Jennie spent her days sitting in an overstuffed arm chair in the living room, a side table piled high with books; a large magnifying glass and gooseneck lamp in near constant use. She wore tailored print dresses in muted tones, button down cardigans with seed beads and pearlized buttons no matter the season or how warm the room, her tiny lap hidden by a varied selection of lap robes from Turkey. Lap robes. How that phrase caused me first consternation, then glee. Lap robes! How strange and delightful — a lap wearing a robe.

Whenever we visited my father’s childhood home, I invariably and immediately perched on a footstool by Jennie’s side. Too young to understand mathematical concepts, I struggled in that stifling room to pay close attention to all she wanted to tell me about the world.

It wasn’t only the grand scale of her mind that intrigued; I recall fascination with the thickness of her masculine glasses, similar in size and shape to those my father wore. Her blue eyes were razor sharp, bright and clear, peering out from a face that seemed to have more wrinkles than it did skin.

There was a dark, velvety mole on her cheekbone. Knowing it was rude to stare, I furtively examined that raised splotch of darkened pigment as she spoke, longing to feel it, to see if it was as soft and cushiony as it looked.

I scorched my fingers during the lighting of candles on her last birthday. The ninety-nine candles crowding together on the round cake were so closely placed that as we lit one another nearby by would sputter to life. Working as a team, my sisters and I lit them with short, cardboard matches that burned down quickly to scorch all our fingers. By the time all were lit, some had burned down so low they were nearly extinguished by the stiff, white frosting that held them upright. Others sagged, flames melting neighboring candles in the middles, disaster seeming imminent. Jennie rallied and tried to blow all the candles out, but I could see how disinterested she was in celebrating her birthday. I contributed my breath, drawing a huge gulp of air, cheeks puffed out, loud and joyful exhales, concerned that if any candles remained lit, none of us would get our wishes granted, ever.

That was in November. The following July, when I was seven, Jennie declared she was tired and went to bed, refusing food and water despite her niece’s pleas. My father was called on to help but Jennie refused to eat even the smallest morsel, sup even the tiniest sip.

Despite my mother’s disapproval, when Jennie died in her sleep, my father took me with him to the Aunts’ house. He watched as I strode down the hall to Jennie’s room. It was mid-afternoon on bright summer day, her room dark and stifling. Jennie lay on her back, eyes closed, the shape of her bird frail body scarcely visible under the covers. Her face looked so odd without the ginormous spectacles magnifying her eyes. I stared at her, willing her to twitch, to show some sign of life, to open a glittery eye. Knowing I had only this one chance, my mind horrified that I was going to touch a dead person, my hand crept across the pillow towards her face.

Here at last was my chance to touch that mole. It was soft, I remember, but not warm or cushiony at all.

We four sisters each got to choose something of Jennie’s to keep, I wanted a soft orange crochet skirt and sweater set that Jennie had made. My older sister wanted it too, arguing that it didn’t fit me. I didn’t care and didn’t relinquish my claim. My mother intervened, giving Cheryl the sweater, me the skirt. During my troubled teens, I gave the skirt to Goodwill. An act I since regret. I would like to have that bit of crochet now, to wrap this book in.

none